The Dungarvan Board of Guardians decided at their meeting on 1 January 1847 that no further people could be admitted to the Workhouse as it was overcrowded. It was reported to contain 739 people on that date. 200 people were waiting to enter, eighty of whom were to be chosen and accommodated in the bathrooms and stable. At their next meeting the Guardians were asked to supply extra accommodation as the Workhouse was 'crowded to excess.' The Medical Officer, Thomas Christian, recommended that there should be no further admissions because of the overcrowding and the prevalence of bowel complaints. On 16 January there were 766 inmates in the Workhouse.

The Dungarvan Board of Guardians decided at their meeting on 1 January 1847 that no further people could be admitted to the Workhouse as it was overcrowded. It was reported to contain 739 people on that date. 200 people were waiting to enter, eighty of whom were to be chosen and accommodated in the bathrooms and stable. At their next meeting the Guardians were asked to supply extra accommodation as the Workhouse was 'crowded to excess.' The Medical Officer, Thomas Christian, recommended that there should be no further admissions because of the overcrowding and the prevalence of bowel complaints. On 16 January there were 766 inmates in the Workhouse. The Rev. William Wakeham, [1] the curate at Kinsalebeg and secretary to the local relief committee, wrote to the Commissioners in early January enclosing a subscription list and looking for a grant. He informed the Commissioners that the committee had distributed weekly barley meal and Indian-corn in quantities from ½ stone to 2½ stone. Two tons of meal were distributed weekly amongst 250 families (18 lbs. per family per week). 'Gratuitous aid will have to be afforded to the infirm and those incapable of labour...Such relief it is proposed to give by issuing tickets for soup in those cases with gratuities of meal.' [2]

Richard Musgrave of Tourin House suggested to Sir William Stanley that a new edition of Count Rumford's book on feeding the poor be printed. Musgrave also informed him that at Grange in the Ardmore relief district he was distributing soup to the destitute. Forty-six families were each given 4½ lbs of soup 'as thick as a pudding.' This was achieved at very little expense and he appealed for a grant to continue the work. [3]

A. H. Leech the Treasurer of the Ardmore Relief Committee wrote to the Commissioners. He noted the:

'sad distress and destitution which prevails in this district, as well as the state of our funds...The district comprises the parishes of Ardmore Grange and Ballymacart, containing 32,000 acres - a large proportion of which is barren mountain, thickly inhabited by paupers - The population amounts to 15,000, about 8,000 of whom are solely dependent upon the potato crop. Of this latter number...upwards of 1,200 are totally destitute either from age, infirmity or widowhood. There are on average six deaths weekly arising from cold and want. The Poor House...now contains eight hundred and crowds of poor are refused admission, the stables and sheds are already occupied.'

Leech also noted that only one-tenth of the able-bodied poor were employed on the public works. According to him there were no resident gentry in the area, inferring that there was no source of employment. The public works were therefore the only source of employment available. Leech wanted to break with regulations to allow his committee to distribute food at a reduced price. The committee's funds were down to £200 and he appealed for as much aid as possible. [4]

A report in a Waterford paper commented on the suffering of the people in Dungarvan:

'You cannot walk abroad for one moment that you are not appealed to by scores of poor creatures...exhausted from hunger...their tottering steps and emaciated countenances would at once convince you of the truth of their soul-sickening story. On Sunday last there were five funerals almost at the same time in Abbeyside...from morning till night you are alarmed by the cries and miseries of hungry creatures.' [5]

Towards the end of January 1847 the Guardians ordered that 'guard beds' should be put in the stables and coach house. This would increase the accommodation in the Workhouse to 800. If further room was required galleries would be constructed in the dormitories, based on plans from the Poor Law Commissioners. On 23 January A.H. Leech, the Clerk at Ardmore Glebe, wrote to the Commissioners on behalf of the Ardmore Relief Fund. A long subscription list was enclosed which amounted to £285.5.3. It was signed by the secretary, William Crawford Poole M.D., and the chairman, Simon Bagge. [6] Lord Stuart de Decies contacted the Commissioners to know what funds were available to the Villierstown Relief Committee to employ the local women in knitting and spinning as there was very little work for women on the public works. The Commissioners agreed to match any funds raised locally. [7] On 27 January the Poor Law Commissioners wrote to the Dungarvan Guardians enclosing plans for temporary sheds for accommodation. They also noted that Mr. Burke, the Assistant Commissioner, had informed them that there was no suitable building available for rent in Dungarvan as an auxiliary Workhouse (see chapter 9). On the same date George Hilla printer in Dungarvan, wrote to Sir Randolph Routh, the Commissary General:

'Sir, I beg to inform you that there is no gratuitous relief given at the soup Depot here. Their boiling is but three times a week, and the quantity only 120 gallons, whilst their funds amount to about £300. The Poor House is crowded to excess, about 168 over its number. Hundreds are starving and several died in this locality from starvation.'

Hill suggested that no further money be given to the Dungarvan Relief Committee until they had used up existing funds by helping the destitute and by giving daily relief. He also warned Routh to beware of fictitious subscriptions. [8]

At a meeting of the Guardians on 28 January 1847 Beresford Boate suggested that each pauper who was unable to get into the Workhouse should get a half-pound of Indian-meal daily. He commented on the 'numbers of paupers, to the amount of some hundreds, during the last three weeks, and 200 on this day, having been refused admittance into the Workhouse, from want of room, and those persons being in a most destitute and starving condition.'

In February it was said that Dungarvan had a greater prevalence of disease than any other part of Ireland:

'In fact it beggars description and outrivals Skibbereen. Every day is seen issuing from the Workhouse gate the dead cart with three, four or five of its dead inmates. The deaths in the Workhouse are nothing, comparatively speaking, to the immense number outside its doors. If something is not done, and that quickly, two thirds of the population must unquestionably perish.' [9]

A member of the Dungarvan soup committee wrote the following letter to the Cork Examiner:

'Allow me in your columns to lament that the necessities of this town and neighbourhood have not been sufficiently brought under public notice, pressing though they be. It is true that private individuals have made, and are making, efforts, in many cases beyond their means, for the salvation of the lives of the people; but their exertions have been unsustained by that aid from without, which has fallen so opportunely in other localities, and in default of which the small fund raised here must soon be expended, with little prospect of renewal from persons themselves suffering under diminished incomes and increased prices. And why are the privations of our famishing people unannounced - borne, too, as they are with a patience and an absence of outrage which are as much beyond example as they are beyond all praise? Do not the Workhouse and the fever hospital acknowledge a frightful mortality, which, unhappily, is not confined to those institutions, but pervades every lane and all the surrounding country? Do not the streets by day and night resound with the wailings of the cold and hungry, who, unable to procure admission even to what were the stables of the over-crowded Workhouse, have been forced out of their lanes and from the neighbouring mountains into public observation? Have not deaths taken place from starvation - and hundreds of deaths from that most prolific cause, disease, engendered and rendered fatal by insufficient and unwholesome food? Is not the fisherman unproductively employed on the public works, a burthen on the food market, instead of a contributor to it?...What have our rulers been doing, for on them will be placed the onus?' [10]

In early February the Medical Officer reported that it was mostly old people and young children who were dying in the Workhouse 'many of whom entered in a hopeless state.' He asked the Guardians to introduce rice into the Workhouse diet and one ton was ordered from Liverpool. On 8 February George Hill wrote a further letter to the Commissary General once again complaining about relief given to the poor in Dungarvan: 'The destitute receive no relief, unless from persons who have already subscribed their quota to the immense sum collected.' He also referred to an article in the Waterford Mail of 15 January 1846 as an example of what could happen to the funds of local relief committees: 'And further bear in mind when Mr. Fisher went, the meal committee closed under an alleged robbery of the money. I printed the reward in which persons' names were put down without their consent.' [11] On the same date Charles Trevelyan (Chief Secretary of State in the Treasury Department) wrote to Sir Randolph Routh. He noted that 'Mr. Shiel has applied for the establishment of a Government depot at Dungarvan, which is of course out of the question; but you could advise the committee to send a cargo to that place.' [12] James Power of Mount Patrick, Kilmacthomas, wrote to Sir William Stanley secretary of the Relief Committee, informing him that the Bonmahon Relief Committee could not raise sufficient funds and had decided to borrow £300. This money was used to purchase wheat which was ground into whole flour and sold to the poor at cost price. 'By this means they have been enabled to sell an excellent quality of food, at a price generally 2d and sometimes 3d the stone beneath that charged in the huxter shop.' [13]

A. H. Leech of the Ardmore Relief Committee contacted the Commissioners informing them that they were finding it impossible to obtain sufficient food in the area to meet the demand. He asked if they could purchase Indian-meal at the government depot in Cork. Leech stated that there were 900 families on their books requiring relief, for whom they required 15 tons of meal a week (32 lbs. per family a week).

'This week we were only able to procure six tons of Indian-meal and in consequence of the anxiety of the poor...Yesterday our depot was broken into and the Police assaulted. The people are in general bearing their privations and sufferings with wonderful patience but such cannot be expected to continue.' [14]

On 25 February the Medical Officer reported that the deaths in the Workhouse were almost all from dysentery and diarrhoea and that many suffered from dropsy because of the prevalence of bowel complaints. The Guardians decided that those paupers from the East Division who could not obtain accommodation in the Workhouse could return to their homes and come to the Workhouse each day for rations. Because of the severe overcrowding two of the Guardians were asked to enquire about renting a store in Dungarvan as an auxiliary Workhouse. At this period there were 858 inmates in the Workhouse, 258 over its capacity of 600. In late February Richard Ussher of Cappagh House and Chairman of the Whitechurch Relief Committee wrote to Sir William Stanley. He enclosed a subscription list for £145.15s, which sum he stated was insufficient to meet the destitution of the area.

'Yellow Indian-meal is now two shillings and ten pence per stone in our markets and many poor creatures are unable to purchase it, and try to exist on meal of turnips daily. Such is their destitution, that about 30 women have been employed in one day grubbing up the roots of turnips, in a field of mine, which my sheep had eaten down for food.' [15]

Public Works Schemes

These schemes were run by the Board of Works and included the construction of roads, harbours, piers and drainage schemes. Those wishing to work on a scheme were issued with a ticket. The wages paid to the labourers, about ten pence, were below the average. This was to prevent people who already had jobs leaving for higher pay on the public works schemes. A new Public Works Act was passed in the latter part of 1846. Under this act the power of local committees was reduced considerably, with the Board of Works and the Treasury having increased powers. New schemes had to be examined by various officials and then had to obtain the sanction of the Treasury. This new procedure meant that there was a considerable delay in starting up schemes. The Temporary Relief Act of 1847 provided relief through the setting up of government-sponsored soup kitchens. It operated from February 1847 to the end of September.

These schemes were run by the Board of Works and included the construction of roads, harbours, piers and drainage schemes. Those wishing to work on a scheme were issued with a ticket. The wages paid to the labourers, about ten pence, were below the average. This was to prevent people who already had jobs leaving for higher pay on the public works schemes. A new Public Works Act was passed in the latter part of 1846. Under this act the power of local committees was reduced considerably, with the Board of Works and the Treasury having increased powers. New schemes had to be examined by various officials and then had to obtain the sanction of the Treasury. This new procedure meant that there was a considerable delay in starting up schemes. The Temporary Relief Act of 1847 provided relief through the setting up of government-sponsored soup kitchens. It operated from February 1847 to the end of September.

The Board of Works published a map in their annual report for 1847 showing public works in progress around the country. In county Waterford a variety of projects are depicted. A pier or harbour is marked at Ballinacourty and Ballinagoul. Seven Coastguard stations are marked along the coast between Tramore and Youghal. A drainage scheme is shown in the vicinity of Dungarvan, to the west of the town. Various land improvement schemes are shown throughout the county. The largest group was six schemes in the Drum Hills. The Waterford Freeman criticised many of the schemes taking place around the county, in particular the new hospital road in Abbeyside (Strandside North) which was in a worse condition after the public works scheme.

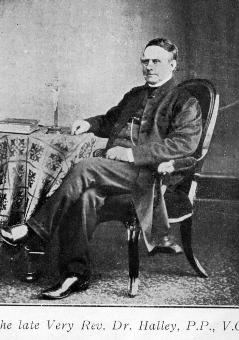

One of the more well-known relief schemes was that called 'Father Halley's Road.' This road began at Two Mile Bridge near Dungarvan and continued over the Drum Hills to Clashmore. The road was named after Father Jeremiah Halley, the parish priest of Dungarvan who instigated the project. [16] As well as the road, several bridges were constructed. On one of these is a limestone plaque with the following inscription:

'Very Revd. J. Halley P.P. Dungarvan caused this road and these bridges to be executed in the year of the Famine 1847.'

The Situation Worsens

By 13 March 1847 there were 1,458 inmates in the Workhouse. The situation was similar in Lismore Workhouse. The number of inmates there had increased from just over 180 in early 1846 to in excess of 600 by March 1847. [17] On 18 March the Medical Officer in Dungarvan reported that he had sent increased numbers of people to the Fever Hospital in Abbeyside:

'That institution is likely to be closed on account of the great many patients at present there. I beg that measures may be taken to reduce the number of inmates to about 500. This would afford space for the dangerous cases.'

The Guardians agreed to reduce the numbers as suggested. It was decided that the healthier inmates would receive out-door relief. The public works schemes had ceased on 20 March 1847. The Guardians noted that

'over 2,000 persons appeared to apply for relief...Destitution in this Union is enormous and therefore request the Commissioners to put the Act for Temporary Relief into operation without any delay, in as much as the great part of the Public Works have ceased.'

The Guardians were worried about the desperation of the people: 'From the great number of persons surrounding the Workhouse premises and scaling the walls that Mr. Boate J.P. do forward a requisition for the Military and Police to be in attendance at the Workhouse this day.' According to Woodham Smith the Scots Greys (dragoons) were called to the Workhouse and the crowds dispersed. [18]

At an extraordinary meeting of the Guardians on 22 March it was agreed that a memorial should be sent to the Lord Lieutenant asking that arrangements for the operation of the Temporary Relief Act be put in place immediately - 'The discharge of the men from the public works on this day will increase the destitution and hourly deaths from starvation before existing to a frightful extent.' They concluded by stating that if action was not taken there would be 'a fearful increase of crime and aggression by the starving population.' On 26 March Benjamin Boate, secretary of the Abbeyside Relief Fund, sent a letter to Sir William Stanley enclosing a subscription list. It was collected by the ladies' sub-committee for the rural district of Abbeyside, and also included the eastern part of Dungarvan parish. Both these districts incorporated a population of about 4,000. 'Our soup relief list which commenced on the 19 December 1846 at first consisted of about 1,500, but lately the numbers have increased so much that it became necessary to afford relief on a more extensive scale.' Boate stated that they had collected £122.8.0, with further money from the Central Relief Committee at 36 College Green, Dublin, who donated £30, the Quakers' Committee £25, and the Committee of 16 Sackville Street £15. [19] On the same date Andrew Carbery, secretary of the Dungarvan Soup Relief Fund, wrote to Sir Randolph Routh. Carbery wrote that the soup relief fund amounted to £251.17.4.

We have duly secured two gratuitous grants over from the London Relief Committee of £100 worth of bread and stuff and the other from the Quakers' Dublin Fund - £20 worth. The destitution in this town is enormous - in addition to our proper inhabitants of 4,600 poor... the town is overcrowded with strangers; paupers from all parts of the Union in addition. [20]

The Medical Officer reported that he had taken over the stables as fever wards and the cases of dysentery had decreased only to be replaced by gastric fever. The Guardians ordered that the agents of the British Relief Association be contacted to ascertain whether they would permit provisions to be sold from their local depots 'at first cost' to the committee of the East Division then being formed under the Temporary Relief Act. Towards the end of March the numbers in Dungarvan Workhouse had dropped by several hundred to 828. By the end of March fever and dysentery were widespread in Dungarvan. The better off were now contracting fever: 'Many of our shopkeepers' families are dangerously ill with fever.' In Ring and Old Parish it was reported that there were eight deaths a day. 'Coffins are becoming a luxury - bodies are being kept five or six days without interment and ultimately they are obliged to be buried wrapped up in a bundle of straw or hay, to keep them from public gaze as they are hurried to the grave.' [21]

In early April the Medical Officer reported that fever was on the increase. The Poor Law Commissioners wrote to the Guardians giving details of how to disinfect the clothes of those who had contagious diseases, recommending steeping them in warm water in which potash had been dissolved and then drying them in a high temperature.

Mr. Foster, a Commissary Officer in Dungarvan, sent a letter to the Guardians on 7 April stating that he was authorised to sell provisions to relief committees 'or to persons who will retail them for charitable purposes and not for profit.'

The Waterford Freeman reporting on the area around Dungarvan noted that:

'The poor are dying like rotten sheep, in fact they are melting down into the clay by the sides of the ditches...The bodies remain for whole weeks in those places unburied. In a corner of the vegetable shambles, a man was dead for five days.'

The paper also referred to a poor woman who carried the dead body of her son around the town in a cart hoping to collect enough money to buy a coffin.

Our venerated and zealous pastor, Doctor Halley, lost no time in procuring the assistance of two additional curates. Oh, this is the time to test the value of a good clergyman, when he has night and day to be in attendance on the dead and dying...I am informed that the Rev. John O'Gorman, Abbeyside, has to attend from 12 to 15 sick people every day; from morning till eleven o'clock at night he is engaged in administrating the last Sacrament to the sick and dying. [22]

The Cork Examiner of 14 April reported that the Duke of Devonshire's agent had filled the pound in Dungarvan with distrained cattle. This was an indication of how bad things were as the article noted that it was 'the first time ever the noble house of Cavendish ever seized a beast for rent.'

A crowd of labourers called to Father Halley's house in Bridge Street appealing to him to obtain work for them. He asked them not to resort to violence or public disorder and stated that he would have work for them on the following day. On the following day he arranged for 400 men to be employed picking stones at Abbeyside beach at one shilling a day. [23] In Killongford, Kilrossanty, Comeragh, Kilnafrehan etc., the stock of potatoes was used up and the farmers were eating their seed potatoes. The Guardians asked the Relief Inspector to apply immediately to the Commissioners for an advance in aid of the rate struck by the Guardians.

They stated that:

'It is most important that funds should be provided for the expense of hiring and fitting up and in some instances erecting buildings for the formation of soup kitchens, provision depots etc., and with the view of laying stores of provisions in order that no unnecessary delay may take place in relieving the pressing and daily increasing distress produced by the reduction of the numbers before employed on the Public Works.'

The Board of Health contacted the Guardians concerning a letter they had received from Doctor Coughlan and the local magistrates in Kilmacthomas. This noted the prevalence of fever and lack of accommodation for fever patients and that the Mining Company of Ireland had offered a building as a district fever hospital.

In Lismore the Guardians took steps to ease the overcrowding in the Workhouse and asked the Parish Priest, Father Fogarty [24] to lease his barn as a temporary fever hospital. The Cork Examiner sent a reporter to the Lismore area to report on the effect of the Famine on the local people. His report, comprising of several pages, was printed in the Cork Examiner of 3 May 1847. Each day he saw hundreds of starving and badly clothed people on their way into Lismore to obtain some meal or bread. In Lismore he saw a pit being opened in a newly acquired graveyard, where forty bodies were interred that week. The reporter praised the work of the Lismore Relief Committee, particularly its chairman Sir Richard Musgrave, and Father Fogarty. He noted that a number of local landlords tried to help their tenants. Those on the Chearnley estate at Salterbridge between Lismore and Cappoquin, were supplied with seed oats and rye and no rent was collected from them. However, not all landlords were so sympathetic to the plight of their tenants. The reporter was shocked at how Arthur Kiely of Ballysaggartmore treated his tenants:

'Arriving at Ballysaggartmore an awful sight was before my eyes, I found twelve to fourteen houses levelled to the ground. The walls of a few were still standing but the roofs were taken off, the windows broken in, and the doors removed. Groups of famished women and crying children still hovered round the place of their birth, endeavouring to find shelter from the piercing cold of the mountain blast, cowering near the ruins or seeking refuge beneath the chimneys. The cow, the house, the wearing apparel, the furniture, and even in extreme cases the bed clothes were pawned to support existence. As I have been informed the whole tenantry, amounting with their families to over 700 persons, on the Ballysaggartmore estate, are proscribed.'

In contrast the following report on John Kiely (brother of Arthur) of Strancally Castle appeared in The Cork Examiner, dated 6 January 1847:

'Far different indeed is the conduct of John Kiely Esq. of Strancally Castle, whose liberality to the poor of his parish is commensurate with his extensive property. He has, at present and for the last season, employed the people, is busily and solely engaged in diffusing comfort and plenty among them, so that there is no one in the parish of Knockanore who can say that he is hungry or distressed at the present moment. To evince his feeling still more, he has killed three of his best cows and distributed them among his labourers...with plenty of vegetables of all kinds...this gentleman has between Poor Relief Committees and incidental employment, expended £1,000 for the last 9 months.'

On 24 April 1847 Andrew Carbery, secretary of the Dungarvan Relief Committee wrote to Sir William Stanley, secretary of the Relief Committee in Dublin. Carbery complained that the work:

'is left to a few of the Guardians, the Parish Priest and one of the Protestant clergymen. We are abandoned by all the rest of the Committee appointed by the Lord Lieutenant. As to the Subscription list, I sent you from Dungarvan £252; this was raised in January 1847 after our subscription and aid for 1846 was out. It was raised by Doctor Halley and myself, Chairman and Secretary. I pray the Commissary General to dispatch us aid for the Town of Dungarvan, quick as possible, as our funds with all the aid we could get from other quarters is out. Save that, this day sent us from the Quakers of Waterford in Meal; those gentlemen sent us deputations twice here. And aid twice to help to extend our relief to our people who are out of employment those six weeks, in addition to the strangers flocking in and our destitute widows and orphans. Our Town is one of the worst in Ireland in its overcrowded state: fever and dysentery in every second house.'

Carbery also noted that Dr. Halley had been appointed chairman of the electoral division committee established by the Lord Lieutenant. Carbery himself had been appointed treasurer: 'You can therefore have no hesitation in sending us aid to our Town subscriptions of £252.' He concluded by stating that he was 'daily and hourly very busy in attending to the testing of names for relief under the Temporary Relief Act.' [25] In April the Guardians ordered that a temporary fever hospital be erected at Aglish for patients from the East Division of Aglish. Doctor Drew was appointed to look after it. These sheds were constructed with timber and canvas.

Around the same time the Guardians decided to co-operate with the Waterford Guardians in establishing a fever hospital in Kilmacthomas. Doctor John P. Coughlan was appointed Medical Officer. On 30 April Andrew Carbery wrote to Mr. Hanley, secretary of the Poor Relief Committee, Dublin Castle. He informed him that their provisions and aid were almost gone and that he would like to obtain supplies on credit until the government grant arrived. 'One days delay will be Death to our numerous poor here. This aid will scarcely suffice for us in this Town - till the Temporary Relief Act comes into operation.' [26]

A letter to the Cork Examiner referred to the deaths of two people from hunger at the quay in Dungarvan and complained of the attitude of the better-off to the poor. The writer felt that they should 'look to the frightful and dangerous condition of these poor creatures...from which malignant pestilence might find its way to their own door. And here let me observe, that every rich person, that got the fever in this town, died.' It was said that about 12,000 people would be on the outdoor relief list for the Dungarvan area. [27] There were complaints about the official relief committee in Dungarvan who had done little but build up an office full of paperwork. The same source stated that:

There are some gentlemen (whose estates are not 8 miles from this town) carrying on their clearance system of exterminating their poor cottiers...Groups of these moving skeletons crowd the shops of our town endeavouring to procure a little assistance to relieve their famished children, whose cries would pierce a heart composed of adamant. [28]

Around this time it was reported that Richard Musgrave had reduced the rents of his tenants at Ballintaylor by 30 per cent and had distributed green crop seeds to them. However not all landlords were so accommodating:

Some of our neighbouring landlords are acting very cruelly towards their poor tenants. At Cuscham over 14 houses were thrown down, and at Curabaha, in the parish of Kilgobnet, 9 houses were tumbled. There were 10 houses razed to the ground at Abbeyside. In these places over 140 human beings have been cast homeless...many of them now begging about the streets. [29]

An 18 year old male was found dead by the roadside at Affane, his legs had been partially eaten by dogs. It was remarked that 'such scenes are now becoming so common that people think nothing about them.' [30] The people were becoming desperate and on 19 May a large crowd gathered outside Father Halley's house threatening to kill and eat his cattle if he did not find food or work for them. [31]

The Central Board of Health wrote to the Guardians in May noting that they wished to provide temporary fever hospitals at Dungarvan, Aglish, Bonmahon and Kilmacthomas. The Board were going to recommend to the Lord Lieutenant that Doctor Christian be employed as Medical Officer for Dungarvan, Doctor Drew for Aglish, Doctor Walker for Bonmahon and Doctor Coughlan for Kilmacthomas. Each of them to receive five shillings a day. The following is a list of the temporary hospitals in the Dungarvan Union.

May 22 - Dungarvan: to serve Dungarvan, Whitechurch East, Modeligo, Seskinane, Colligan and Kilgobnet. The hospital to cater for 100 patients with four nurses and two ward maids.

May 22 - Aglish: hospital for 20 patients with two nurses and one ward maid.

May 22 - Ballylaneen: hospital based in Bonmahon to cater for 30 patients with two nurses and one ward maid.

June 2 - Ardmore: to serve Ardmore, Grange, Kinsalebeg and Clashmore. The hospital in Ardmore to cater for 50 patients with two nurses and one ward maid.

At the Guardians meeting of 3 June Andrew Carbery proposed that in future individual members of a family should not be allowed enter the Workhouse unless accompanied by the rest of their family. Those inmates who did not comply would be discharged. As the numbers in the Workhouse increased this proposal was amended. Families could obtain relief but at the same time remain out doors. On 8 June the Poor Law Commissioners wrote to the Guardians stating that they had received a letter from the printer George Hill, in Dungarvan. Hill informed the Commissioners that a poor man who had been refused entry to the Workhouse on 27 May was subsequently found dead by the roadside, outside the gates of the Workhouse. The Commissioners asked the Guardians for further details on the case. The Clerk replied that the man's name was not on the Workhouse books and that as the place was full no one had been admitted except a few orphans. The Commissioners wrote a further letter reminding the Guardians that it was the Master's responsibility to admit urgent cases to the Workhouse. However, they accepted the explanation given by the Guardians.

On 10 June, Francis Sheehan, the manager of the National Bank in Dungarvan, wrote to the Guardians informing them that their loan of £500 had been sanctioned. This was on condition that the chairman and two of the Guardians act as securities. The Clerk was directed to reply that the Guardians would not become individually responsible for the loan. At the Guardians meeting on the following week, Robert Longan proposed the following motion:

'I hereby give notice that I shall on Thursday the first day of July next move a resolution to the effect that this House be cleared of its inmates and closed, in as much as the Union is indebted to the amount of £1,500 and there is no prospect of such a collection of the poor rate, lately declared, as would enable the Board to liquidate the debt.'

John McCormack of Dungarvan wrote a letter to the Cork Examiner in June 1847 commenting on the potato crop: 'I can assert with confidence that there has not been for many years a more cheering prospect and that the potato crop in the parishes of Whitechurch, Ardmore, Dungarvan, Kilgobnet, Ballinacourty, Ballinagoul and Gurthnadiha, never looked more promising...farmers from these localities have informed me that there is not the least appearance of blight up to this time.' [32]

On 26 June the Clerk wrote to the Commissioners informing them that it was impossible to collect the rates for the East Divisions. He stated that only a portion could be collected and asked that the Commissioners reply immediately as 'The trades people and contractors usually supplying the Workhouse have refused any further supplies until the bills already due them are liquidated.' At the Guardians meeting of the following week Robert Longan agreed to postpone his motion to close the Workhouse pending a reply from the Commissioners concerning the rates.

In early July it was remarked that the potato crop in the Dungarvan area was good: 'the potato crop never looked so luxurious. Yesterday being our market day here, great quantities of new potatoes were exhibited for sale.' [33]

Andrew Carbery and Father Halley were praised for their work in helping the poor:

'They devote their time from morning until 3 o'clock in giving out-door relief to our starving poor...they have employed several men to distribute carts of lime and whitewash brushes to the people in every street and lane.'

As a result of their efforts fever had decreased. The local Church of Ireland minister, the Rev. Morgan Crofton was also praised:

I cannot pass over in silence the praiseworthy manner in which the Rev. M. Crofton has exerted himself since the commencement of this awful calamity in clothing the naked and visiting the sick, I am well aware his private charities to reduced housekeepers far exceeds his public acts of benevolence - too much praise cannot be given to this Rev. clergyman for the pains he has taken to relieve a famine stricken people. [34]

The Relief Commissioners contacted the Guardians on 31 July looking for the accounts for the end of the temporary relief operations. They were to collect the government boilers, sacks and implements from the relief committees. On 14 August the Relief Commissioners contacted the Chairman of the Board of Guardians informing him that because of the distress in the Union they would allow an extension to the period for temporary relief. This relief was operated on a reduced scale for a limited period after 15 August. In early September it was proposed that the school be moved out of the Workhouse to a house in Dungarvan as the Guardians were expecting a large increase in admissions to the Workhouse when the outdoor relief ceased on the 12th. No suitable property could be found in the town so it was decided that alterations would be made to accommodate them within the Workhouse. Sleeping galleries were to be erected in the attics and the stables would be used for the boys until wooden sheds were constructed to house 300. The Commissioners suggested that the Guardians build permanent accommodation and that if they wished they would have their architect draw up the plans.

Around this time the local Poor Law Inspector described the paupers in Dungarvan as 'wretched a class as can well be imagined, what struck the most was that the applicants exhibited as filthy, sickly and starved appearance as those who sought admission in the Western Unions of Cork during the last winter and spring.' [35]

By 25 September the number of inmates had risen to 592 and the following week 750 were refused admission. By the end of the month the numbers had increased to 718.

On 5 October the Guardians received an inventory of items which belonged to the Grange Relief Committee: two boilers containing 100 gallons each, one of which was cracked. A scoop with a beam and weight, 71 lbs, 41 lbs, 21 lbs, 1 lb, 21 lbs, 1 lb, ½ lb, and twenty one barrels which came from Dungarvan. Later in October R. Godfrey, the Clerk of the Ardmore Relief Committee wrote to the Guardians enclosing a list of utensils used at their soup kitchen which were to be handed over to the Guardians: 3 boilers, 2 covers, 1 fire shovel, 3 grates and door frames, 1 gallon can, 1 water can, 2 quart measures, 1 sweeping brush, 2 sets of weights and scales and 180 meal barrels.

On 21 October over 400 people arrived at the Workhouse gates looking for relief. The police were called to keep order and to allow the Guardians to pass through. It was remarked that: 'These poor creatures whose cabins the landlords tumbled down are in a most deplorable state of misery and forced to lie at the side of the roads. Several hundred have been evicted.' [36]

In early November the Master reported that they would need to build two large ovens at the Workhouse to enable them to bake biscuits which would be distributed to those on outdoor relief. The following week the Medical Officer commented that he had found it necessary to convert a shed next to the stables as a ward for whooping cough.

On 25 November the Master gave details of a planned riot by the inmates, the purpose of which was to force the Guardians to increase their rations. He suggested that the Guardians should take immediate action to prevent such occurrences. It was decided that the leaders should be reprimanded and if they repeated their behaviour they would be discharged from the Workhouse, and their families who were on outdoor relief would be denied it in future. The Relief Officers of the various districts were ordered to distribute Indian-meal at the rate of 1 lb. to each adult and a ½ lb. a day to those receiving half rations. On 2 December the Medical Officer reported that the number of inmates in the Workhouse was excessive and would lead to the spread of disease. He suggested that the relieving officers only admit the most needy cases pending the repairs to the store. Discipline was becoming a major problem in the Workhouse. The Master noted in December that he had to withdraw the soup from the men because of the disorderly state of their wards. A row in the women's ward resulted in one women 'having her eye nearly taken out.' Two of the women involved in the disturbance were handed over to the police.

In early December a letter was sent to the Cork Examiner from Dungarvan complaining of the way in which the poor were being treated:

It is harrowing to my feelings to behold hundreds of these starving people in this inclement season...outside the pay clerk's door in Church street...until such time as this paid functionary is pleased to dole out to each...7d for their weeks support, or rather, to procure for them a lingering death...The Guardians have made a contract with a certain baker in this town to supply them with biscuit for the use of the poor, who were receiving 7d a week, and in lieu of which the 7d is now stopped. The kind of stuff the poor are getting is as black as an old shoe and as hard as slate; in my opinion, such wrongs committed on the poor will cry to heaven for vengeance, and a day of reckoning will come. I cannot remain longer a silent spectator and overlook such injustice inflicted on a famine stricken people. [37]

At this period the state of the Dungarvan Union was described as 'disastrous.' The rate collectors were finding it impossible to collect rates from the small occupiers and in one area the rate collector had to be accompanied by 200 police. [38] The people were desperate to obtain food and resorted to theft to keep alive. On 24 December two sacks of flour were stolen from Roger Baker's shop in main Street. On the same night a heifer was taken from Thomas Healy of Knockateemore and eight sheep were taken from his uncle, William Healy. Both had been robbed a few weeks previously. [39]

On 23 December 1847 the Clerk had to strike off the books '830 heads of families' as the outdoor relief had come to an end. By 30 December the numbers in the Workhouse had increased to 916.

Alexander Somerville (1811-1885) visited Ireland in 1847 and published accounts of his journeys throughout the country in the Manchester Examiner. He visited the Clonmel and Dungarvan areas. Somerville reported that corn was brought to Clonmel from Waterford and other sea ports to be ground in the mills there. He stated that Clonmel was the headquarters of the Scots Greys who were employed in guarding the meal carts.

He decided to accompany one of the meal carts on part of its journey to Dungarvan. An escort accompanied them consisting of one officer, two sergeants and 25 men. The carts were drawn by one horse and had from 12 to 14 cwt. of meal and the driver received one shilling per cwt. Somerville was surprised that these carts were able to make the long journey on bad roads as Charles Bianconi had ceased operating his coaches between Clonmel and Dungarvan. On the way he met 61 carts travelling towards Dungarvan. In his reports he particularly emphasised the brisk sale in guns and pistols in the Clonmel/Dungarvan areas and that few travelled without arms. Somerville gives very little information about Dungarvan other than mentioning the large landholders such as the Marquis of Waterford and the Duke of Devonshire. He noted the significant building improvements carried out in Dungarvan by the Duke but was not impressed with the management of the Duke's farmland. However, he admitted that he did not have enough information to comment further on the matter. [40]

References

Author: William Fraher