My terms of reference concern the 20th century in Ardmore, but readers will probably be interested in the list of 19th century ship wrecks in the neighbourhood, and also the very interesting account of Perkin Warbeck's engagements.

1823 Hope (a Youghal ship)

1850 Grace of Newcastle

1860 Echo

Peig Thrampton (year unknown)

1865 Certes (of Malta)

1865 Sextus (of Malta)

1875 Scotland

1881 Elizabeth of Whitehaven in Whitingbay

1895 Jeune Austerlitz of Cardiff

1998 Dunvegan.

The above list of ships and the account of Perkin Warbeck's adventures in Waterford are taken from "Shipwrecks of the Irish Coast" 1105-1993 by Edward J. Bourke.

On the 23 July 1497 Perkin Warbeck pretender to the throne of England and Maurice, Earl of Desmond besieged Waterford with 2,400 men. Waterford was held by forces loyal to the king. Eleven ships arrived at Passage East and two landed men at Lombards Weir. One enemy ship was bulged and sunk by the ordnance from Dundory, Warbeck escaped to Cork and there to Kinsale pursued by four ships. He then went to Cornwall, still followed by ships loyal to the throne. A cannon with reinforcing rings typical of the period was dredged from the Suir and is on display in Waterford.

Incidentally, in an account given to the Royal Society of Antiquarians of Ireland by Westropp in 1903, he says "In 1497, Perkin Warbeck, the pretender to the English crown occupied Ardmore Castle and sent thence to summon the city of Waterford to surrender. At Ardmore, he left his wife in safety and marched to besiege the city that refused his claims." This account is somewhat at variance with the previous one but is nevertheless interesting.

According to the Ardmore Journal 1988, seventeen ships were lost off Ardmore 1914-1918, fourteen of them in 1917. In most of these cases, the attack occurred ten miles or more out at sea and the survivors were picked up and brought elsewhere, so the incidents passed unnoticed in Ardmore. The Folia and the Bandon, however, were quite close inshore when torpedoed.

The wreck of The Teaser on Curragh strand in March 1911 has been well documented. This abbreviated account is based on an article by Donal Walsh in 'Decie'. September 1982. The Teaser was bound for Killorglin, Co. Kerry with a cargo of coal and left Milford Haven on 16th March. She had a crew of three and all three were lost.

A very strong south-easterly gale had blown up and the boat was blown on to the rocks at Curragh. John O'Brien sighted her at 5am on 18th March, got as close as possible and saw three men on board but could not communicate with them on account of the noise of the storm. He reported to the Ardmore Coastguards and a message was sent by telegraph to the Helvick Life-boat. Three coastguards, Thomas Bate, Richard Barry and Alexander Neal arrived in the meantime with the rocket apparatus. All three men on board the boat had taken to the rigging. Five rockets were fired; some missed but the men on board failed to operate the others which did reach the boat. Coastguards Barry and Neal tried to swim to the ship along the rocket line, but failed in the attempt.

Fr. O'Shea C.C. Ardmore then came into the story. At his instigation a boat was brought from Ardmore by horse and cart and he called for volunteers to go out to the Teaser. Coastguardsmen Barry and Neal, Constable Lawton, William Harris of the Hotel, Patrick Power and Con O'Brien farmers and John O'Brien fisherman answered the call and were able to get alongside the Teaser by hauling themselves along the rocket line and rowing at the same time. Wm. Harris, Constable Lawton and the two coastguards boarded her. The men on board were still alive but only barely and unfortunately they dropped one survivor into the sea while taking him down, but Barry and Neal dived in and rescued him. Fr. O'Shea administered the last rites. The bodies were laid out in Michael Harty's barn and according to an account by Johnny Larkin, Curragh, two were buried in Ardmore and the Captain's body brought home to Wales.

The incident got great publicity and on 13th April 1911, the Committee of Management of the R.N.L.I. meeting in London, awarded the Gold Medal of the Institution to Fr. O'Shea and appropriate awards to all the other participants. The Carnegie Hero Fund trust awarded all of them as well, and then on 2nd May 1911, Fr. O'Shea and his party were decorated by King George at Buckingham Palace.

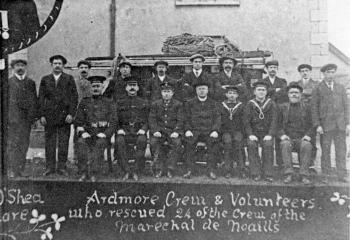

On 12th December 1912, the Marechal de Noailles of Nantes left Glasgow for New Caledonia, a French Penal Island in the South Pacific. She carried a cargo of coal, coke, limestone and railway materials. There was a crew of twenty besides the Captain and First and Second Mates. The beginning of the voyage was eventful with seven days being spend at Greenock waiting for an improvement in the weather; a further seventeen days off Aran Island, Scotland; then venturing down the Irish Sea but about sixty-five miles north of Tuskar having to retrace the voyage, this time to Belfast Lough. At last, they really got going and were a few miles from Ballycotton, when the wind strengthened. They turned about; the Captain fired distress signals; eventually the ship was blown ashore three hundred yards west of Mine Head.

On 12th December 1912, the Marechal de Noailles of Nantes left Glasgow for New Caledonia, a French Penal Island in the South Pacific. She carried a cargo of coal, coke, limestone and railway materials. There was a crew of twenty besides the Captain and First and Second Mates. The beginning of the voyage was eventful with seven days being spend at Greenock waiting for an improvement in the weather; a further seventeen days off Aran Island, Scotland; then venturing down the Irish Sea but about sixty-five miles north of Tuskar having to retrace the voyage, this time to Belfast Lough. At last, they really got going and were a few miles from Ballycotton, when the wind strengthened. They turned about; the Captain fired distress signals; eventually the ship was blown ashore three hundred yards west of Mine Head.

Helvick Lifeboat responded to the distress signals, but could not approach her. The keeper of Mine Head lighthouse, Mr Murphy telephoned the Ardmore Coastguards, and the rocket crew assembled. Coastguards Barry and Neal, J O'Brien, J Mansfield, J McGrath, P Foley, J O'Grady, M Curran, J Quain, P Troy, M Flynn, Con Byron, Sergt Flaherty, Constable Walsh and Fr. O'Shea. As the roads were too bad for the rocket wagon to travel, the crew carried the apparatus fourteen miles on foot to the wreck and arrived about 2am. The apparatus was assembled; the first rocket passed over the vessel, but the crew did not know how to deal with it.

Meanwhile, one sailor had been washed overboard and J Quain encountered him at the bottom of the cliff and explained the workings of the rocket apparatus, by sign language. With the aid of a megaphone, he instructed the rest of the crew still on the ship how to work the Breeches Buoy, and all the men came ashore.

Four had been injured during the night by flying spars and were unconscious and anointed by Fr. O'Shea. All were eventually taken to Dungarvan. Some months later, Fr. O'Shea had a most appreciative letter from Captain Huet, Morlaix.

No doubt, it was an unforgettable experience for the Ardmore men, tramping for hours in the dead of night with their apparatus which looked as if it wasn't going to have the desired effect; then the joyful break-through the language barrier and being surrounded by a group of men "quacking like ducks" as one of them put it. So it is not surprising that the name Marechal de Noailles is remembered years afterwards in Ardmore. (The most of this account is taken from the article by Donal Walsh in Decies. September 1982.)

The Nellie Fleming from Youghal figured twice in shipwreck stories. The first Nellie Fleming went aground on Curragh strand in December 1913, having in the mist mistaken their location. The Ardmore coastguards and Youghal and Helvick Lifeboats were in attendance, but the crew hoped to get her off. Finally, when the water gained on the boat, the crew abandoned ship and returned to Youghal by the life-boat. Next morning, the owner came and concluded that the boat was going to be a total wreck and handed her over to Lloyd Agent, Mr Farrell of Youghal.

The Nellie Fleming from Youghal figured twice in shipwreck stories. The first Nellie Fleming went aground on Curragh strand in December 1913, having in the mist mistaken their location. The Ardmore coastguards and Youghal and Helvick Lifeboats were in attendance, but the crew hoped to get her off. Finally, when the water gained on the boat, the crew abandoned ship and returned to Youghal by the life-boat. Next morning, the owner came and concluded that the boat was going to be a total wreck and handed her over to Lloyd Agent, Mr Farrell of Youghal.

A group of locals bought the cargo of coal from him and formed a coal company to resell the coal. Jack Crowley with three other lads recalls being sent by his father, the local school master to bring home ¼ ton coal for the school, by donkey and cart. They weren't upset being at the end of the queue which comprised farmers from Grange and Old Parish coming for the cheap coal. He referred jokingly afterwards to the "Curragh Coal Co-op" as being the first Co-op in Co. Waterford. (This account is condensed from that of James Quain in the Ardmore Journal.)

An interesting fact which emerges from the story of the Teaser and of the Marechal de Noailles was, the crew's ignorance of the life-saving equipment and how to use it; and also of the fact that people in general were ignorant of the principles of life-saving and resuscitation. A bystander in Curragh has said, at least one of the men was still alive while being brought ashore, but clearly, nobody knew how to deal with the situation and apply artificial respiration.

The Folia (6704 gross tonnage) was sunk off Ram Head in March 1917. Seven of the crew were killed in the explosion; the others took to the life-boats and eventually made their way to Ardmore and reached it as last mass had finished, so there was a large crowd around. The R.I.C. took a roll-call outside the Hotel on Main Street. Many people provided food and clothing and arrangements were made to transport them to Dungarvan, where they were taken that evening in a fleet of cars.

In the Ardmore Journal 1988, James Quain in his account of the incident includes an interesting letter from a member of Dr Foley's household, Glendysert. "All the people took some of the crew to each house. We had five, three English, one American (the doctor) and one Dane. Some were without boots, all without socks, some without coats and so on. After looking after creature comforts (they were of course without food since the night before, with the exception of the biscuits, with which each boat is provisioned) they were anxious for music, so we put on the gramophone for them. I believe they danced and sang up at the convent. Sr. Aloysius played for them." The letter-writer also says of the attack on the boat, "When they had taken to the boats, the captain of the submarine who was very courteous, came up to them and told them they were all right and to row into Ardmore, 4½ miles away."

The article by James Quain goes on to say, "Some months passed before the salvage began to float in. Wooden barrels of oil were picked up by the Receiver of Wrecks and later sold. Sides of ham, loose or in boxes, I cu yard in size came into Ardmore and elsewhere along the coast. Large slabs of tallow about 3 feet by 2 inches thick floated ashore in boxes or single slabs. These were seized by the locals and used for making candles as paraffin oil for lamps was very scarce.

As the Folia is such a large vessel 430ft in length and is located only four miles off Ram Head, it has been dived on many times, although it lies in about 120ft of water. According to Lloyds, the ship was carrying a general cargo, but a large number of brass items has been recovered.

According to the Dungarvan Observer 8th March 1980 "During the Summer of 1977 two salvage vessels 'Taurus' of Hamburg and 'Twyford ' of Southampton were working on the lines.......... Recently in Ardmore, divers were seen in the area.......... Divers from Tramore, West Cork and Dungarvan were involved.......... One of the divers Cormac Walsh said they were working as a hobby on another wreck the 'Counsellor' which is hundreds of yards away from the Folia and about 130ft deep.

The Bandon (summary from Ardmore Journal 1988). On 12th April 1917, the Bandon sailed from Liverpool for Cork under the command of Captain R.F. Kelly. On the evening of Friday 13th an unlucky day to be at sea, when the ship was off Mine Head, she was struck by a torpedo on the port side and immediately began to sink, with a loss of twenty-eight lives. The four survivors including the captain were in the water for over two hours. Following a message from Mine Head lighthouse, they were rescued by motor launch and taken to Dungarvan. The explosion was heard clearly on shore, and when the smoke had cleared away, the Bandon had disappeared.

The late Johnny Larkin of Curragh wrote his own account. "On the 13th of April 1917, she was sunk 2½ miles south of Mine Head and about four miles from the Curragh shore. I saw her go down in less than half a minute. She was sunk by a submarine, according to the British, but I think the crew did not know what sank her. She went so quick some said she was sunk by a mine or two mines tied to a chain.

The spring of 1947 will long be remembered in Ardmore for its severity. Snow rarely falls here, but that year, the place was absolutely snowed in, with men having to go out and dig trenches in order to let the bread van in.

It was at this period that the S.S. Ary, a ship of 40 tons displacement left Port Talbot , with a cargo of coal for the Railway Company at Waterford. The Captain was an Estonian, Capt. Edward Kolk and the fourteen other crew members were of various nationalities. The weather worsened and the cargo of coal began to shift and in spite of all efforts, the list got worse and the crew had to abandon ship somewhere off the Tuskar Rock. They had no oars, no food or drink in the two life-boats.

When Jan Dorucki, the sole survivor woke from sleep he found himself surrounded by dead men, who had all died from exposure and being frightened, he pushed them all overboard. For two days more, the life-boat drifted on and eventually came ashore on the Old Parish Cliffs. Jan was in a dreadful condition, but somehow he managed to climb the cliff and dragged himself to Hourigans' farm-yard, where the dog found him at dawn. He was brought in and wrapped in a blanket and eventually brought to Dungarvan Hospital. A point to remember is that people did not have telephones nor motor-cars at this period.

Cait Cunningham who was on duty at the hospital, when he arrived gave a heart-rending account of it to Kevin Gallagher who has had it published in his column in The Dungarvan Observer. He remained in a critical condition for days and eventually had to have both his legs amputated. During his stay the language barrier proved a great obstacle, but Nurse Cunningham says, a Polish officer arrived from England and so did Jan's father; and a Polish phrase book and dictionary they brought, were a wonderful help. He returned to Poland after twelve months.

Meanwhile, the bodies of Jan's companions were being washed in along the coast from Ardmore to Knockadoon. Willie Whelan of Ballyquin found a body on the beach; he brought it to Ardmore, where it was identified as being that of a Spaniard and was buried in Ardmore graveyard.

During the course of that week-end, the other eleven bodies were brought to Ardmore. According to the inquest, they all died of exposure. I remember seeing the coffins stacked up outside the Fire Station. Later on, they were buried in one grave in a corner of the graveyard. The funerals began at 2pm and each coffin was brought up in turn, in the hearse provided by Kiely's of Dungarvan. Rev Fr. O'Byrne P.P. and Rev. Warren, Rector of St. Paul's said the graveside prayers.

Fifty years later on November 1st 1997 Canon O'Connor of Ardmore and Rev Desmond Warren (nephew of the Rector of fifty years before) presided at prayers at a newly refurbished grave and headstone erected by the people of Ardmore. Donald Lindenburn, whose father George was in the Ary came from Swansea; he had his father's naval record book; he had seen war duty on the Atlantic and the Pacific, so it was tragic and ironic that he should perish on the short trip across the Channel to Ireland. He placed a family wreath on the grave and so did Jim Spooner from the British Merchant Navy. The service concluded with the lone piper's lament by Mr Michael McCarthy.

Later on in the afternoon, John and Billy Revins took the Welsh visitors out on Ardmore Bay, where another wreath was set afloat to the memory of the fourteen members of the Ary crew. These last paragraphs have all been condensed from Kevin Gallagher's account in the Dungarvan Observer.

The Fee des Ondes a French boat was wrecked in Ardmore in October 1963. It was blown in to Carraig a Phúintín and all efforts of Youghal Life-boat to get her off failed. It was with difficulty, the skipper was persuaded to leave, even though the boat had been holed by the rock and began to take in water.

The Fee des Ondes a French boat was wrecked in Ardmore in October 1963. It was blown in to Carraig a Phúintín and all efforts of Youghal Life-boat to get her off failed. It was with difficulty, the skipper was persuaded to leave, even though the boat had been holed by the rock and began to take in water.

The Cork Examiner of October 28th 1963 says "Two Frenchmen were rescued by life-boat, and seven crew, one of fifteen years old on his first voyage, by rubber raft in a sea drama, off the beach at Ardmore, Co. Waterford yesterday morning. They were the crew of the 300 ton trawler Fee des Ondes out of Lorient, which went aground in poor visibility just before dawn and which was subsequently severely damaged by rocks and pounding waves.

Youghal life-boat had been launched and life-saving rocket man, Jim Quain, was alerted, raised the alarm and fired the maroon which brought out the full crew. The crew came ashore by rubber dinghy but the Captain P Maletta and his mate E Dantec refused to abandon ship for a considerable time. They were all taken to the village and Mrs Quain provided hot food and clothing. An abiding memory of hers, is, besides the salt water even seeping down the stairs, was the incident of the crew sitting around her dining room table where a cask of Beaujolais from the vessel, containing about twelve bottles or so was ensconced. They asked her for glasses and imbibed the lot without as much as asking her would she like a glass, never mind a bottle. Lloyds later offered to recompense them for their hospitality, but they declined to accept.

The boat being accessible at low water, it was visited by all and sundry during the following days. The jocose poem by Dan Gallagher gives a pretty good but perhaps exaggerated account of what happened.

"If you want the position of 'Receiver of Wreck'

All you require is a bit of neck.

A hacksaw, a crowbar a pony and cart

A low spring tide and you're ready to start.

But, hold on a minute, do you know where to go?

To the strand at Ardmore, when the tide is low.

'Tis there you will find her, a fine boat was she,

'Ere being driven ashore by the wind and the sea.

The sailors and looters worked there, side by side

With one eye on the wreck and one eye on the tide.

They came day and night, they came by the score

From Piltown and Youghal, Old Parish, Clashmore.

They came armed with crowbars, with hammers and saws

With tractors and trailers, flouting all civil laws.

Now the early prospectors got the best of the spoil

they got nets by the dozen and ropes by the mile,

Whiskey, gin, rum and brandy and lovely French wine,

They spent the night drinking and all felt sublime.

Some bottles without labels, distilled water contained

But they like the others, to the bottom were drained.

There were bottles of lotion for salt water rash.

One man drank a bottle and wiped his moustache.

There were oil coats and trousers and boots there to snatch

With pillows and mattresses and blankets to match.

Sure the night shift itself was a sight to behold

With torches on deck and down in the hold.

Some more daring than others, climbed up on the mast

Cutting off rope and pulleys that were firmly made fast.

But the ladder on the foremast was the envy of all

('Tis still lying there, for the mast down did fall).

Both the mast and the ladder would be useful, you see,

To rig up the aerial when we get the T.V.

The farmers were there, day in and day out.

Looting pulleys and chains; they'd be useful no doubt.

The women were there, looking after their men,

With flasks of hot soup, and tea now and then.

And when they were ready and home did retire

They had bags full of wood and corks for the fire.

For in lighting the fire, the black corks they say

Put up a fine blaze in a marvellous way.

There was an odd little bit of jealousy too

When the others got better than me or than you.

A wreck-laden horse-cart, one day on the strand.

Had the French Flag trailing on the sand.

If De Gaulle had seen it degraded that way,

A declaration of war would be here any day.

The poor men with bags didn't get much at all,

With their lack of equipment and payload so small.

To compete with the others he hadn't a chance,

With their tractors and trailers, they led him a dance.

Some need not fear Winter, though storm winds may blow

And the ground be covered with frost and with snow,

For the wood piles all mounting round many a home

Not to talk of scrap iron for dealers who roam.

There'll be many bright fires, between you and me

While the family sit round them watching T.V.

Yes, she was a fine boat when she entered the bay

But she's now like the turkey on St. Stephen's Day.

And now that she's gone, to the Lord we must pray

To send us another, without too much delay.

At the end of a storm in January 1984, the Anne Sophie from Lorient landed under the Cliff near Mine Head, Ballycotton life-boat stood by and the eight crewmen were lifted off by an R.A.F. helicopter, working in gusts of 90mph at night, under the cliff face.

The Maltese-owned 180 foot crane barge Sampson was driven ashore at Ram Head, during a south-easterly gale on 12th December 1987, while being towed from Liverpool to Malta. The tow parted and could not be connected, owing to the gale. The crew of two were rescued by R.A.F. helicopter from Brawdy. The tug Zam Tug 2 arrived from Cork the next day and remained on stand-by for several hours, before giving up the idea of re-floating the crane ship.

There were initial fears that diesel oil from the badly holed vessel would have polluted the neighbouring beaches but such a disaster was averted by the prevailing winds. Jim Rooney (formerly of Strand Bar) got to the crane by using a rope and in order to claim salvage, stayed on board in horrendous conditions for forty days. Food and changes of clothing were lowered to him regularly during the period. The incident occasioned great publicity; Jim gave several newspaper interviews and was much photographed, but it is highly doubtful if he benefited anything from salvage money after all.

A large propeller from the Sampson was mounted outside the Commodore Hotel in Cobh in 1991. We still have the wreck at Ram Head.

Author: Siobhan Lincoln