The summer of 1920 saw the formation of an active service unit (A.S.U.) or flying column. The column was continually on the move through Comeragh, The Nire, Colligan, and the Drum hills. George Lennon led the column, which was under the overall command of Pax Whelan and brigade staff. Lennon spent some time studying tactics with other Munster columns and considered the Decies column to be among the best.

The summer of 1920 saw the formation of an active service unit (A.S.U.) or flying column. The column was continually on the move through Comeragh, The Nire, Colligan, and the Drum hills. George Lennon led the column, which was under the overall command of Pax Whelan and brigade staff. Lennon spent some time studying tactics with other Munster columns and considered the Decies column to be among the best. They were drilled almost weekly by an ex-British army man, Sean Riardon of Dungarvan, and in action showed remarkable disipline. Their self-control was evident at Pilltown in November, 1920, where they held their fire and disarmed thirty British military with the loss of only two English dead. Owing to the increasing number of raids on their homes the flying column were by August, 1920, living "on the run". Patsy Whelan, father of Pax, got so tired of answering the door to admit R.I.C. that he sent his key to the barrack so that they could let themselves in.

Men on the run slept in the open or stayed at houses such as Walshes of Ballyduff, Walshes of Ballymullagh, Mansfields of Crowbally, Cullenanes of Kilmac, Powers of Glen and Powers of Garryduff. Mansfields put up men in a small loft over the kitchen and a large one in the yard. Men also slept in the kitchen settle or on sacks before the glowing embers of the open fire. Farmers such as Mike Mansfield of Crowbally sometimes bought equipment for the column out of their own pockets.

Dispatch riders kept the different battalions and the column in touch with one another and with other brigade areas. Jerry Fitzgerald carried his messages hidden in a penknife slit made in a piece of dried cow-dung and rode a requisitioned horse named Silver Tail on his cross-country missions. On seeing R.I.C. or military Jerry slipped the cow-dung to the ground where it was never noticed.

On entering a house the column men often scanned the skyline, i.e., the pieces of bacon hanging from the ceiling hooks, in order to gauge how well equipped a house was to feed them. The table at Powers of Garryduff was of such quality that this house was known as the "Gresham". A dispatch might then contain the information that Lennon, Whelan and Keating were staying at the Gresham.

The brigade carried out weekly raids on the mails during the summer of 1920. Crown mail was read and then marked "censored by I.R.A." was sent to its destination. By August the R.I.C. had been forced to provide all mail with an armed police escort. On 8 August, 1920 this escort was disarmed at Dungarvan station. Pat Keating disguised as a naval officer caught the R.I.C. detective sergeant, who was awaiting the mail train, off guard, took his revolver and placed him in the w.c. where Volunteer James Drummy guarded him. The raiding party of Pat Burke, James O'Keeffe and Paddy Power remained hidden at the end of the waiting room. When the party of four R.I.C. came from Dungarvan to meet the train they were held up by the waiting I.R.A. and disarmed. This incident caused the British to abandon the regular mail service and use a light aeroplane to carry their letters.

An R.I.C. patrol was held-up at Kilmacthomas and in an exchange of fire a policeman was killed and arms, a bicycle and some documents were captured. On 15 August, an attempt to rush Ardmore police barrack failed but gave the brigade the idea for the Piltown ambush of November. The postman in Ardmore was Patrick Hurtin, a Volunteer, who was later killed by Black and Tans. It was decided that Hurtin would hold the barrack door open when he went to deliver the mail. A picked group of the Ardmore battalion under Jim Mansfield intended to rush the open door and disarm the police inside. The I.R.A. were crouching in position as Hurtin approached the door but they were spotted by a policeman's wife who gave the alarm. The R.I.C. opened fire through the barrack windows and sent up Verey lights to summon aid from the marines, whose station was about four hundred yards distant, and from Youghal barracks. Willie Doyle, Paddy Cashen, Declan Slattery, and Dick Mooney, with other local Volunteers, saw to it that the marines' position was kept under fire so that the original attacking group were able to retire in good order. This action began at 8 a.m. It was 10 a.m. before all the battalion had reached open country.

Three lorry loads of military numbering sixty men arrived from Youghal and took up positions around the two crown bases. Meanwhile a party of Black and Tans from Dungarvan who had been ambushed at Kiely's Cross were making their way across country to Ardmore. These were fired on as they neared the village and in the course of a running fight two of the Black and Tans were hit. This action took place at about 4 p.m. The flying column then retreated to the Knockmealdowns and began to consider the plans for an ambush at Pilltown.

Mount Melleray which is cradled by the Knockmealdown mountains was always a port of call for the Decies brigade. Confessions were heard by the monks who gave the column a bite to eat while they listened to an account of what was happening. The parochial clergy gave moral support to Sinn Fein and Monsignor Power, P.P. of Dungarvan, had his furniture taken by Black and Tans because of his public support for the brigade. The Augustinian friars at Dungarvan also gave spiritual assistance when called upon. In fact, Eddie Mansfield a brother of Mick and Jim, was during these years studying for the priesthood with the Augustinians in Rome. Cooneys of Carrigroe, a regular port of call for men on the run also had a son in the Augustinians. As a matter of interest it could be mentioned that there were two Mansfield girls in religion, one with the Presentation and the other with the Mercy Order. Column men were of course expected to join in the family rosary in the houses that gave them shelter. It will be seen that the image of an anti-clerical, semi-communist force does not correspond with reality. Writers who stress this side of the I.R.A. probably had little real contact with men "on the run."*

Column men were interested in military affairs and liked to read about the Russian revolution but their literature was as a rule confined to a British army manual. The writings of Lenin were not easy to come by in the Comeraghs. Mick Mansfield was an avid reader but his books were popular novels, military histories, or accounts of the Great War. He was often to be seen reading in a corner while his comrades played cards or cleaned their weapons.

The pressure on the R.I.C. was maintained when one of their patrols was disarmed near Ardmore by Willie Doyle, Paddy Veale and Jimmy Fitzgerald, of the Kinsalebeg company. After this Lisgarow ambush the R.I.C. ceased to bear arms in the area. In July, Mick Shalloe of the Brickey company acted as co-ordinating officer for a raid on Youghal which resulted in the shooting of Head Constable Ruddick of the R.I.C.

Having grown tired of their tension-filled existence, the R.I.C. vacated all their rural barracks in Co. Waterford. Local companies burned and destroyed the abandoned barracks. Generally this operation went off without a hitch but Michael Cronin and Richard Tobin were badly burned while setting fire to Clashmore barrack. Barracks destroyed at this time included those of Ring, Clashmore, Kiely's Cross, CoIligan, Villerstown, Kilmonan, Ballinamult, Knockanore, Tallow, Killmanahan, Leamybrien, Stradbally and Kilmacthomas. Only those protected by the military were manned by police, Cappoquin and Lismore.

Regular crown forces including military, Black and Tans and marines, now moved in to the Decies. They were billeted at Lismore, Cappoquin, Dungarvan, Clonkoskerane House, and Ardmore. Naval patrols sometimes landed men on the coast and were even known to shell suspected I.R.A. positions. Because the normal mail service had been rendered ineffective an aeroplane was now used by the enemy to carry dispatches between their posts. Martial law and curfew were enforced. Houses had to post lists of inmates on their doors and it was difficult to travel from place to place without a permit. Many donkeys and cows were shot when they failed to respond to a challenge.

To counteract the stranglehold of forces on the brigade area the flying column moved from place to place taking pot shots at tenders as opportunity offered. A favourite I.R.A. sniping position was the hill overlooking Youghal bridge. This was named Chocolate Hill by the British after a similar position which figured in the Great War.

Jim Mansfield devised a system of smoke signals using wet grass, furze and a blanket. Mirrors were used for daylight signals in the mountains.

On a September day in 1920 a Crossley tender dashed through Dungarvan and sped into the country on a terrorising mission. Pax Whelan calculated that the Black and Tans would return via the Cappoquin road and decided to ambush them at Brown's Pike about two miles from Dungarvan. Local men, George Lennon, Pat Lynch, Ed. Kirby, and Pakie Cuillinane went to the brigade arms' dump at Coolnagour and picked up four rifles, four revolvers, ammunition, and about twenty home-made cocoa-tin bombs. When the tender arrived at the Pike fork roads it was fired on and a number of bombs were landed in it, inflicting injuries on the Black and Tans who did not stop but retreated at full speed to the shelter of their barrack. This was the last foray made by a single tender in the Dungarvan area.

Previous experiences had shown the brigade staff that military lorries could be expected from Youghal if the crown positions at Ardmore were attacked. They now decided to mount a simultaneous assault on the Ardmore R.I.C. and marine positions with a view to luring a lorry out from Youghal. The brigade engineer prepared an ambush position at Pilltown near Ardmore. A trench was dug across the road and trees were felled as an additional barrier to motorised transport. Jerry Fitzgerald got word to the column who came down from the Knockmealdowns to join the Ardmore battalion. Men were detailed to block the Dungarvan and Cappoquin roads so as to prevent reinforcements arriving from the east and north. A local unit went to ferrypoint to guard against a naval landing.

The main body of the column and other picked men took up their positions at Pilltown at 8.30 p.m. At about 9.45 column men threw Mills bombs at the Ardmore positions and, leaving the local company to keep up the diversionary attacks, returned to Pilltown. The Ardmore barrack acted as expected and sent up Verey lights. Close to midnight, signals from lookouts informed the men at Pilltown that a military lorry was approaching from Youghal.

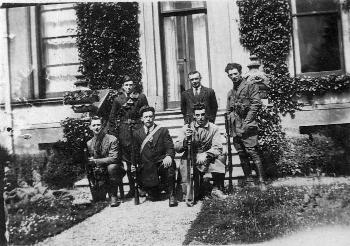

The enemy drove right in to the ambush position and the lorry driver was killed in the first fusilade. The column which included George Kiely, Sean Riordan, Pakeen Whelan, Pat Keating, the Mansfields, and Ned Kirby rushed the lorry. The British ceased firing and threw down their arms. With remarkable self-control the Decies men who now had the military at their mercy held their fire and lined up the British by the roadside. The English were then disarmed. They were next given a dray for their wounded and allowed to make their own way back to Youghal. Enemy casualties numbered two dead and six wounded. Twenty-six rifles, two carbines, Mills bombs, revolvers, and Verey light pistols were captured by the unscathed west Waterfords. The arms were placed in a car named the Grey Ghost of Eddie Spratt's transport section driven by Nipper Johnny McCarthy and taken to Villerstown.

Later in November, 1920, a section of the Flying Column, while on manoeuvres at Rockfield, Cappagh, saw an enemy lorry approaching on the Dungarvan-Cappoquin road. They hastily took up positions and opened fire with rifles. Before firing ceased George Lennon and Seamus Pendergast threw grenades, one of which landed among the military, severely wounding two of them. The enemy numbered about twenty while only six I.R.A. were involved, including Mick Shalloe and Pakeen Whelan.

Every 2nd of the month an R.I.C. patrol crossed the Youghal bridge to bring a pay check to the drawbridge keeper on the Waterford side. On 2 December, 1920, an I.R.A. group waited for this patrol on Chocolate Hill on the Ardmore side of the bridge. They opened fire when the patrol of six R.I.C. were in the centre of the bridge. Prendeville, a policeman, who had been set free at Pilltown, on condition that he resign from the force was fatally wounded and two other members of the patrol were also hit. The enemy who seemed to dread crossing from Youghal into west Waterford opened the drawbridge after this shooting so that no road traffic could enter Youghal from Waterford. The bridge reopened to traffic only after the truce.

On 31 December, 1920, coursing day at Cappoquin, Pat Keating, George Lennon, and Mick Mansfield were recognised and fired on by the R.l.C. They managed to escape, killing one R.I.C. man in exchange of shots.

Looking back over 1920 it is clear that there was plenty of action in County Waterford. The R.I.C. were rendered ineffective, heavy military forces had to be drafted into the county, the majority of enemy barracks were destroyed, the mail service was not allowed to function, and a Flying Column and four battalions were in constant action against the enemy. Of course, 1920 did not see the end of fighting in the Decies. 1921 was to see ambushes at Dunhill, Stradbally, and the Burgery, attacks on crown positions, and many daring exploits including the capture of an enemy plane.

* It should be borne in mind that the Capuchin Annual was a Roman Catholic publication and as such would have been hostile to communist/socialist thinking. Events in the Civil War in Waterford showed that there was a distinct left-wing/communist element within the I.R.A. The precise size of this element is difficult to determine. While it would have been in the minority it was sizeable. (Editors Note)

Author: Fraher, Mansfield, Keohan