The Relief Commission was established by the Government in November 1845. The Commission was directly responsible to the Lord Lieutenant. The brief of the Commission was to collect information concerning the availability of food and the level of distress among the poor and to give relief. Local relief committees were established and usually included the landlord, magistrate, parish clergy, and Poor Law Guardians of the locality. The list of local subscribers to the relief funds was required to be published. The Relief Commission added between one-third to a half to the money raised locally. The Commissioners set up food depots around the country to store imported American corn. If the price of food rose, the local relief committees could purchase this corn and sell it at cost price. The committees were not supposed to distribute free food except to those unfit for work who could not gain entry to the Workhouse. The Dungarvan Relief Committee was established in January 1846. Andrew Carbery was Treasurer and the parish priest, Jeremiah Halley, was chairman. Beresford Boate was secretary of the Abbeyside Relief Committee and Robert Longan was chairman. In July 1846 the Dungarvan committee reported that they had sold 1,420 sacks of Indian-meal (of 20 stone each) at reduced prices from March to July inclusive. 977 poor families (consisting of about five persons on average) were supplied daily with one-seventh of meal at one shilling per stone of 14 lbs. [1]

On 24 February 1846 Arthur Quin, the Medical Officer of Dungarvan Dispensary, compiled the following report on the health of the people: 'Bowel complaint very prevalent, from the use of unsound potatoes. Diarrhoea and dysentery prevalent from the same causes. The number of patients at the dispensary has considerably increased.' At Dungarvan Fever Hospital he noted that fever was more prevalent than usual and that the number of patients had increased by 20% as a result of eating unsound food.

On 26 February Dr. George Walker reported on Bonmahon Dispensary: 'A great increase in fever in the district. From 150 to 200 unemployed in the village of Bonmahon. A considerable increase of fever apprehended from the scarcity and high price of food.' On 4 March the Guardians complained that the Master was giving food to paupers residing in the town and insisted that food should only be given to those living in the Workhouse. In April Andrew Carbery proposed that Union funds 'lying idle in the bank' be used to purchase Indian-meal for the use of the ten relief committees which had been set up in the Union. On 2 May Andrew Carbery sent a printed subscription list to the Commissioners. The money was collected between 19 January 1846 and 2 May and amounted to £349.12.6. The list was printed by a Dungarvan printer, George Hill. The Duke of Devonshire contributed the largest sum of £100. Other contributors included the local gentry, merchants, clergy and professional people. On 25 July Carbery sent an additional list which amounted to £183. The subscribers included Lord Waterford, Sir Nugent Humble, John Kiely of Strancally and Richard Lalor Shiel M.P. [2]

On 26 February Dr. George Walker reported on Bonmahon Dispensary: 'A great increase in fever in the district. From 150 to 200 unemployed in the village of Bonmahon. A considerable increase of fever apprehended from the scarcity and high price of food.' On 4 March the Guardians complained that the Master was giving food to paupers residing in the town and insisted that food should only be given to those living in the Workhouse. In April Andrew Carbery proposed that Union funds 'lying idle in the bank' be used to purchase Indian-meal for the use of the ten relief committees which had been set up in the Union. On 2 May Andrew Carbery sent a printed subscription list to the Commissioners. The money was collected between 19 January 1846 and 2 May and amounted to £349.12.6. The list was printed by a Dungarvan printer, George Hill. The Duke of Devonshire contributed the largest sum of £100. Other contributors included the local gentry, merchants, clergy and professional people. On 25 July Carbery sent an additional list which amounted to £183. The subscribers included Lord Waterford, Sir Nugent Humble, John Kiely of Strancally and Richard Lalor Shiel M.P. [2]

In early May James Power, secretary of the Bonmahon and Kilmacthomas Relief Committee, sent a resolution to the Commissioners. He informed them that Lorenzo Power and Richard Purdy would visit them to apply for aid for the Ballylaneen district. Ballylaneen was part of the Bonmahon and Kilmacthomas relief district. He noted that there was 'a mining population of about 3,000 souls, who principally live in the parish of Ballylaneen though the mine works are situate in Kill parish - some of these are in a state of great destitution in consequence of which the representatives of the parishes of Kill and Newtown have withdrawn themselves from our committee, thus throwing the whole burthen on the small parish of Ballylaneen.' [3]

On 25 May Robert Longan, chairman of the rural relief sub-district No.1 of Dungarvan and Kilrush sent a subscription list of £97 to the Commissioners. He asked the Lord Lieutenant to give them 'as large a grant as possible' as great distress existed in the area and no public works were in operation. Clement Carroll was secretary to the committee. [4] Pierce Marcus Barron, chairman of the Stradbally/Clonea Relief Committee informed the Commissioners in June that there was £149.12.6 to the credit of the committee. 105 families had been given relief the previous week.

Barron noted:

'great destitution exists in this district, in which are comprised the village of Stradbally and Faha and the village and townland of Ballyvoile, containing a population of upwards of 5,300 persons among whom there are a very great number of destitute...and the distress is hourly increasing, and likely to be so, by not having any public works in progress.' [5]

On 4 June Richard Power Ronayne sent a resolution and subscription lists to the Commissioners from Ardmore, Ring, Clashmore, Kinsalebeg and Villierstown amounting to £597.10.11. He referred to the 'numerous and helpless families' which amounted to several thousand people who were in a state of utter destitution. [6]

On 18 June the Parish Priest of Kilgobnet, Michael O'Connor, wrote to the Commissioners as chairman of the 'Kilgobnet, Colligan and Seskinane sub-relief committee.' He enclosed a list of subscribers and referred to the meal which they had been selling at two depots, at a reduced price. He noted that over the previous five weeks they had helped 336 families who comprised of 1,680 individuals.

We apprehend the number will greatly increase, in consequence of a great proportion of the district being mountain on which are located a vast population, principally small cottiers, who, having lost all their potatoes are from their impoverished condition quite unable to purchase food in the Markets and all of whom must be supplied in future by the committee with food at a reduced price. [7]

The subscription list of three pages amounted to £186.10s. However, Father O'Connor stated that the committee had only £49.0.6 to their credit and asked for as large a grant as possible.The necessity for continuing the relief can seen from the condition of the harvest in the Workhouse. Early in August 1846 the Master ordered that the potatoes grown on the Workhouse grounds should be dug up and given to the inmates. However, by 29 August the Master and Medical Officer reported that the potatoes were unfit for human consumption. On 3 September it was ordered that 'a dozen ridges of potatoes should be preserved, for the purpose of trying the experiment of stirring the earth about them with a three-prong fork.' The remainder were to be sold off and the ground cleared and planted with winter vegetables.

Andrew Carbery wrote to Sir Randolph Routh on 1 September concerning oatmeal and biscuits:

'The oatmeal shop here opened by the D.C.G. Dobree for the sale of oatmeal sent here from Clonmel depot is now ordered to be shut up...The state and number of persons here in this locality at present unemployed with large families, that cheap food - heretofore their support, is entirely lost to them...there never was for the last year any period so necessary to apply Government aid to those people as at present. We have a large fishing population here that will require the Biscuit to take to sea to fish - in place of potatoes. We have no mills here - Our bakers day and night at work cannot keep up supply. Our Indian-meal and all others are to be brought by land carriage from Waterford, Portlaw and Clonmel. Our car-men often obliged to wait a day for their orders.'

Carbery added that he and his two clerks had spent all of the previous year looking after the poor and it seemed as if they would have to continue to do so. [8] Carbery sent a further letter to Routh on 14 September enclosing a resolution which contained the following points: It noted that the price of Indian-meal had increased by 50% to £12.10s per ton (1/6½ d. per stone) and was retailing in Dungarvan at one shilling and eight pence per stone. Wages for able-bodied men on the public works schemes should not be less than one shilling a day 'to enable them to support a miserable existence at the present enormous high price of food.' Carbery warned that if the men were made to accept lower pay it would be 'dangerous to the state and peace of Society.' Routh replied to Carbery's letter suggesting that his committee promote the importation of Indian-corn. [9]

The Public Works schemes were meant to cease in August 1846, but the potato blight forced the government to continue with the schemes. In 1846 the finances to run these schemes had to be raised locally, unlike the previous year when the Government paid half the cost. A public meeting was held in Dungarvan courthouse on 17 September to consider setting up public works schemes. On 16 September the constabulary were ordered by the Government to submit occasional confidential reports on the progress of the blight. The following answers were returned:

Q. Is the acreage of potatoes planted in 1846 the same as the previous year?

A. One quarter less.

Q. What proportion of the 1846 crop is affected by the blight?

A. All.

Q. Is the early or late crop affected?

A. Both.

Q. Is the surviving crop fit for food?

A. Very little of it.

The same sad state of the potato crop was no doubt evident to the general populace. Their reaction could only be awaited. On 24 September several thousand people marched to Fisher's Mill at Pilltown, County Waterford. They demanded that the Indian-meal should be sold for one shilling per stone from the mill. It was reported that the crowd later proceeded to the Ferry Point, opposite Youghal, with 'sticks, stones, spades and hammers.' [10] About the same period it was reported that people in Clashmore were living on blackberries. [11] Some days later there was a serious disturbance at Clashmore. A stone-throwing mob of 3,000 attacked the magistrates leaving the courthouse. Their anger was directed against Lord Stuart de Decies over comments he had made at the Sessions:

With some difficulty he got into his carriage, when immediately his servant put the horses into a gallop and flogged them most violently to keep them at the fullest pace. the mob followed in numbers, many of them by a short route, to stop his departure and proceed to extremities, which sir Richard Musgrave, perceiving, a party of Hussars were dispatched for escort and protection. With difficulty they were enabled to keep the mob back and his Lordship fled to Dromana at high speed. On the Hussars return the mob gathered in the churchyard...armed with stones and with most violent yells and execrations against the military they immediately commenced an attack on them. A ringleader named Power from the parish of Grange, was severely sabred, but was carried off by the populace...Several of the horsemen were dangerously hurt, and the force being small, they had to retreat for their lives to Lord Huntingdon's farmyard at Clashmore House which was immediately barricaded.

The Cork Examiner expressed surprise at this attack on Stuart:

'He is a kind and very indulgent landlord, and sets his ground for the value to the occupiers and has 60 men employed at Ballyheeny, draining at which they earn one shilling and six pence a day, besides employing about 300 men on other parts of his estate.' [12]

The Dungarvan Riots

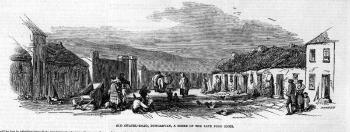

In the minutes of the Dungarvan Board of Guardians of 1 October 1846 there is a reference to two wounded men who had been admitted to the Workhouse. One of them was Michael Fleming from Kilmacthomas. They were among the casualties of a riot which took place on Monday 28 September 1846. [13] A large mob of several thousand had attempted to break into the grain stores on the quay and also demanded employment on public works schemes. The ringleaders, including Patrick Power of Killongford, were arrested and placed in the Bridewell. Later in the day a more militant section of the crowd demanded the release of the prisoners. When their demand was refused they looted a number of bakery shops in the town. The Pictorial Times for 10 October carried an engraving of a crowd breaking into a bread shop in Dungarvan.

In the minutes of the Dungarvan Board of Guardians of 1 October 1846 there is a reference to two wounded men who had been admitted to the Workhouse. One of them was Michael Fleming from Kilmacthomas. They were among the casualties of a riot which took place on Monday 28 September 1846. [13] A large mob of several thousand had attempted to break into the grain stores on the quay and also demanded employment on public works schemes. The ringleaders, including Patrick Power of Killongford, were arrested and placed in the Bridewell. Later in the day a more militant section of the crowd demanded the release of the prisoners. When their demand was refused they looted a number of bakery shops in the town. The Pictorial Times for 10 October carried an engraving of a crowd breaking into a bread shop in Dungarvan.

The 1st Royal Dragoons were called out and chased the crowd up William Street (now St. Mary Street). Events came to a climax at Old Chapel Lane (now Rice's Street, Youghal Road). After repeated verbal attempts by the magistrate to disperse the crowd, the riot act was read. The officer in charge, Captain Sibthorp, gave orders to fire and 26 shots were fired into the crowd. Fleming and Power were seriously wounded. [14]

Four companies of the 47th Foot (The Lancashire Regt.) were sent to keep order in the town. In spite of this ships were prevented from leaving Dungarvan Quay on 1 October because the men hired to load the ships were afraid to do so for fear of reprisals from the crowd. On 5 November the Medical Officer of Dungarvan Workhouse reported that Michael Fleming, one of the men wounded in the riot of 29 September, had died.

On 7 November the Illustrated London News [15] carried a further report on the riot. The article is titled - 'The Late Food Riots in Ireland' and is accompanied by an illustration of the scene of the riot at Old Chapel Lane. The article states that one of the men shot was standing behind the cart featured in the sketch.

'The distress, both in Youghal and Dungarvan, is truly appalling in the streets; for, without entering the houses, the miserable spectacle of haggard looks, crouching attitudes, sunken eyes and colourless lips and cheeks, unmistakably bespeaks the sufferings of the people.'

Article From The Illustrated London News, November 7th, 1848 on the Dungarvan Food Riots (External Link)

Further Reaction

On 7 October a large crowd tried to stop the transport of corn, the property of Mary O'Keeffe and Richard Talbot of Tallow, at Strancally on the river Blackwater. The crowd threatened to throw stones at the boatmen if they did not return to Janeville Quay at Tallow. As a result the boatmen were unable to deliver their cargo to Youghal. Some days later Sir Richard Musgrave, who lived nearby at Tourin House, took the unusual step of writing to the Cork Constitution defending the actions of those involved. He felt that they had been forced into attacking the boatmen as a result of starvation. [16]

Riots were also taking place around the country and the Government reacted by arranging for 2,000 troops, formed into mobile columns, to be sent to the trouble spots. The Waterford Chronicle reported that 16 people had been arrested in the Dromana/Villierstown area 'for intimidating the farmers and others to pay back con-acre rent received by them this year. Those who were committed reached here (Dungarvan) at 7 o'clock this night, escorted by 40 cavalry and about 100 infantry.' [17]

In October a Dungarvan writer to the Cork Examiner asked why the public works schemes which had been passed a month previously had not yet started. The writer praised the local clergy and stated that most of the public works schemes in operation were due to their efforts. He particularly singled out the Parish Priest of Kilgobnet, Father Michael O'Connor: 'Every day regardless of the inclemency of the weather he worked harder, both in town and parish...and now has the satisfaction of having got employment for a large portion of his people.' [18]

The following account titled - 'Benevolence of Lord Stuart de Decies' was published in the Cork Examiner in October:

'We are glad to learn that in promoting the benevolence of his Lordship, the clergymen of the district, both Protestant and Catholic, have been most indefatigable. The exertions of the gentlemen have been devoted to selecting the most worthy recipients of his Lordship's generosity, and, so far as they have proceeded, their efforts have been completely successful. The Rev. William Mackasy, curate of Clashmore and the Rev. Michael Purcell P.P., visited the tenantry on Slievegrine mountain, and after patiently investigating the circumstances...made such a distribution of his Lordship's generosity as completely satisfied the poor people of this locality. In their laudable exertions these Rev. Gentlemen have been zealously seconded by the Rev. Mr. Hickey and the Rev. Mr. Hurley, Roman Catholic curates of this district.' [19]

In November conditions were getting worse in Dungarvan: 'Indian-meal is now two shillings and three pence per stone, and will, it is apprehended, be three shillings per stone before a fortnight elapses, it was but one shilling per stone this time last year, when the labouring man's wages was a shilling per day.' Many of the starving and undernourished people were complaining of severe stomach disorders: 'The complaint is attended by a racking pain in the bowels and a violent discharging of the stomach...so violent was the attack that it reduced them to perfect skeletons in less than 24 hours.' Meanwhile it was reported that Richard Ussher of Cappagh had been selling seed bere and barley to poor farmers at the 'unprecedented low price of two shillings and nine pence per stone.' [20]

In Ardmore people had been working on the public works for over three weeks without receiving any pay. In spite of this they remained calm and it was said that people helped each other by sharing food. There was a new Parish Priest, Father Garrett Prendergast. 'The people are full of joy and begging every blessing for him and his two active assistants, the Rev. Messrs O'Donnell and O'Connor.' The Ardmore Relief Committee expected the government to provide a relief scheme to construct a pier in Ardmore. Up to this period the fishermen had to drag their boats on to the land and it was said that they would not venture out to sea unless the weather was calm. [21]

By early December it was reported that fever had spread at an alarming rate in the Dungarvan area. 'Out of one house in the Old Parish, three persons (of the Lyons family) died in one fortnight - the father, the son and the mother, leaving after them, six orphans who are also lying in fever.' [22]

A meeting was called by the farmers of Ardmore and Grange to try and do something to alleviate the distress in the area. It was held in Grange church. One person commented that: 'the sufferings of the poor in this locality is terrible! Some, who, only a month since, appeared pretty comfortable, are at this moment walking skeletons.' At the meeting Father Prendergast warned that if action was not taken immediately he could not guarantee the peace of the locality. [23]

By 19 December 1846 there were 650 inmates in Dungarvan Workhouse and the numbers were increasing daily. On 21 December the 'Ladies of Dungarvan' started a subscription list to set up a soup depot. The meeting was held in the Courthouse and was attended by the clergy and influential citizens. It was addressed by Father Halley, Mr. Hudson the Seneschal, The Rev. Morgan Crofton the rector, Andrew Carbery, Rev. John O'Gorman of Abbeyside, Doctor Christian, Edward Boate J.P., Father Mooney and Dr. O'Farrell of Dublin. [24] Thirty-six pounds was collected at the meeting 'from the few gentlemen present.' £240.12.0 was eventually raised. Subscribers included the Duke of Devonshire, the Marquis of Waterford, local gentry, merchants and some donations from England. [25]

The Waterford Freeman of 21 December referred to the 'extraordinary exertions' of Andrew Carbery, a Dungarvan merchant, in his efforts to help the poor people of the town: 'Through his exertions the turnpike grievance is likely to be removed, which will be of great benefit to the trade and commerce of the town.' [26] Andrew Carbery had previously reported the following:

'The whole receipt of oats in the town, from September last to the present March did not exceed 1,500 barrels and the receipts of barley do not exceed 900 barrels...I have laid out my money in improving the town and numbers of persons have followed my example. We have 34 vessels from 120 to 140 tons burden, and that for want of corn in the Dungarvan market they are only employed in carrying coals or copper ore.'

References

- N.A./R.P. 4762.

- N.A./R.P. 5219/4762.

- N.A./R.P. 2277.

- N.A./R.P. 2594.

- N.A./R.P. 2897.

- N.A./R.P. 2938.

- N.A./R.P. 3471. 'Rev. Michael O'Connor appears to have built the present parochial residence at Coolnasmear. He had some little reputation as a poet. His efforts generally taking the form of impromptu rhymes in English or Irish.' Parochial History of Waterford & Lismore, 1912. p.138.

- N.A./R.P. 5627.

- N.A./R.P. 5765.

- Field, W.G., The Handbook for Youghal 1896, reprinted by T.C. Field 1973, p.94.

- Woodham-Smith, Cecil, The Great Hunger, p.125.

- Cork Examiner, 26 September 1846, Cork Constitution 26 September 1846. For a more detailed account of this riot see: William Fraher, 'The Dungarvan disturbances of 1846 and sequels', in Brady and Cowman eds., The Famine in Waterford, pp. 137-152.

- Cork Examiner, 2 October 1846.

- Illustrated London News ix, 7 November 1846 p.293.

- Kennefick, J.,'The Famine in the Parish of Lismore and Ballysaggart', unpublished thesis, 1983. p.84.

- Waterford Chronicle, 19 October 1846.

- Cork Examiner, 24 October 1846.

- Cork Examiner , 9 October 1846.

- Cork Examiner, 4 November 1846.

- Cork Examiner, 11 November 1846. Concerning Father Prendergast Canon Power had the following comments: 'Rev. Garret Prendergast, whose practical sympathy with the poor Famine-stricken people is still a living memory, was appointed Parish Priest in the miserable year 1847. During the 'bad times' he distributed food on Sundays to two hundred persons. He was spared only ten years - dying in 1857, and lies buried in Ardmore Church.'

- Parochial History of Waterford & Lismore, Harvey, Waterford 1912. p.15.

- Cork Examiner, 11 December 1846.

- Cork Examiner, 12 December 1846.

- N.A./R.P. 15606.

- Cork Examiner, 28 December 1846.

- This was a toll levied on farmers who wished to sell their produce at the Dungarvan markets. The toll was paid at the turnpikes situated on the out-skirts of the town.